The myriad of animals living on News-Press story teller Amy Bennett William’s rural Alva homestead frequently add context or humor to her essays. This week’s offering, though, places one particularly charismatic creature in the spotlight.

It’s the story behind the family’s aged, outspoken and beloved donkey, who came to be known as, “Burrito.”

Even though I know I don't, I still sometimes hear Burrito as I'm scooping up the horses' feed.

The donkey's voice, a windy, wheezy moan, had been part of my mornings for 15 years. Soon as he heard the bucket's rattle, he'd start calling until I appeared with his grain.

He was the hungriest animal I'd ever known, attacking everything edible - even things that weren't - with the ravenous vigor I associate with cartoon jackals.

I'm sure he never had enough to eat in his youth, which he'd spent among a herd of ranch horses. They'd bullied him mercilessly, to which the crescent-shaped hoof scars and clumps of pulled-out fur attested when I first saw him, cringing in the back of a makeshift corral.

I'd been looking for a protector for my small flock of goats and something small and safe my newborn eventually could ride, when I saw an ad placed by a horse trader in Charlotte County. He'd bought out a ranch and found the donkey in with the cow ponies, he told me over the phone - a "little old busted-up jackass," the cowboys had used for roping practice. He was asking about 50 bucks. I headed out to take a look.

Once I saw him, though, I decided the price was too high. Quivering in a muddy corner on spindly legs, the aged donkey was all eyes and ribs, with a runny nose and bent-back ears, one pierced with a plastic cattle tag.

Without the trader's rope leashed around the panicky creature's neck, there's no way we'd have gotten anywhere near him; he snorted and pulled away in terror as we approached. It was plain this was not the donkey for me, I politely told the trader as I backed toward my car.

But in a pen that small, the horses would kill him, the trader told me; could he just give him to me? In fact, he'd bring him over in a few hours and throw in a bag of feed for my trouble.

And so, Manuel (after the patron saint of mule drivers) joined the family. He fattened right up and tamed right down as his given name morphed into Burrito - Spanish for "little burro." I had no idea how old he was. The first time our vet, Dr. Don Moore, looked at his teeth he guessed at least 15, probably more.

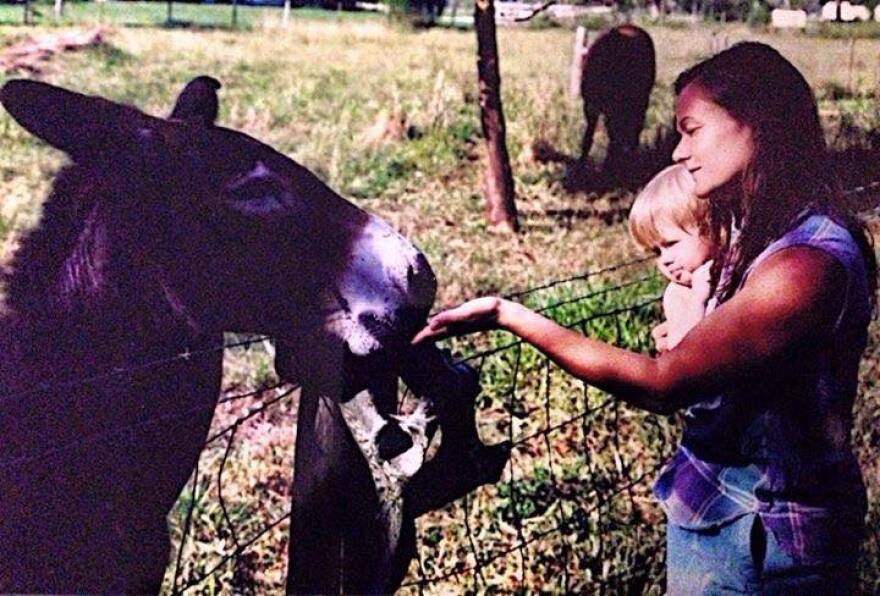

Spectacularly slow and gentle, Burrito was utterly trustworthy with the kids, both of whom got their first-ever equine experience on his fuzzy grey back. The other spectacular thing about Burrito was how he sounded. Forget the hee-hawing of cartoon cliche; this animal was operatic, beginning every morning with hungry, howling runs up and down the scales until someone appeared with the feed bucket.

When we moved to Alva a few years ago, that hunger almost proved his undoing, after he ate so much of a toxic weed his liver failed. But Dr. Moore helped us snatch him back from the brink and he returned to his usual, hungry self, though he couldn't keep much weight on after that.

Still, the old boy seemed happy enough, wandering the pasture in search of green morsels, backing his skinny hindquarters into me, hoping for a rump rub, mooning over our mares and braying for his breakfast.

In fact, once after Dr. Moore was done giving everyone their shots, I’d congratulated him on Burrito's continued existence. He smiled and shook his head. "You know, don't you," he asked, "that someday he's going to just lie down and not get up again and that'll be it?"

Just weeks later, Burrito didn't appear for his evening meal. We found him stretched in his corner of the pasture, not wanting to move.

He awoke the next morning, but only barely. He was gasping, eyes half-lidded.

After we'd dropped Nash off at school, Roger and I headed back to the pasture.

Working with one decent shovel and a pair of clippers for the oak roots, it took us less than an hour to dig his grave. But for the grimness of our task, it would have been pleasant work, a cool, sunny morning under a bright blue sky.

When we were done, I scratched behind Burrito's ears and rubbed under his jaws one last time.

Soon after that, he drew his last breath.

We rolled our old friend into the ground, under a young oak.