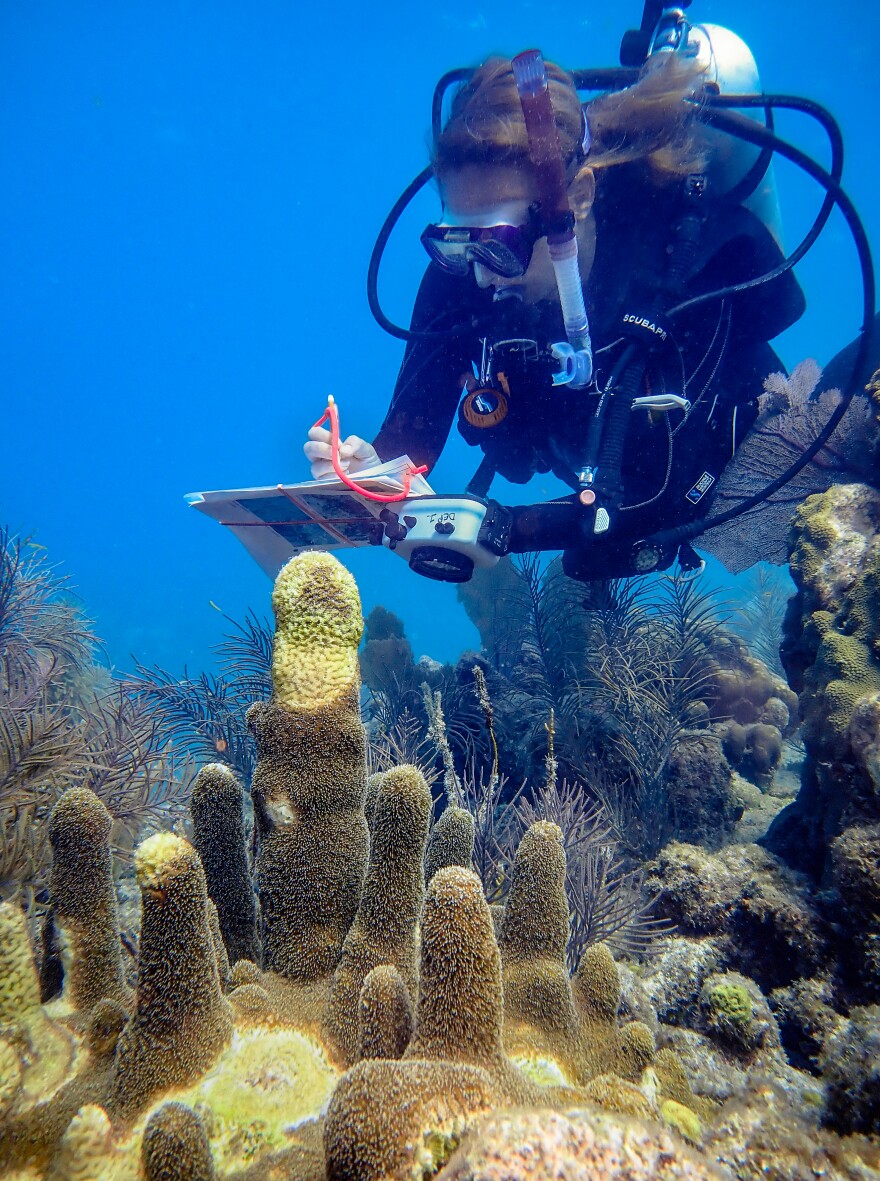

When pillar coral was proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act, coral biologists began a survey and assessment of all known colonies on the Florida reef tract. That was in 2013.

They found and followed more than 800 colonies of the coral, from the Dry Tortugas to Biscayne National Park.

WLRN is committed to providing South Florida with trusted news and information. In these uncertain times, our mission is more vital than ever. Your support makes it possible. Please donate today. Thank you.

They wound up documenting the coral's last days as a viable species in Florida. In 2014 and 2015, reefs around the world, including in Florida, went through an unprecedented bleaching event.

Coral bleaching happens when stress from warm waters makes coral expel the symbiotic algae that provide their food. Shortly after came the death blow: a disease called stony coral tissue loss disease that has killed some corals at a rate that has never been seen before.

A new paper, in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, documents what happened to pillar coral during that time — and finds that the species is "functionally extinct" on the Florida reef. One cause for hope: because pillar coral was being so closely watched and was already known to be rare, biologists began a pillar coral rescue program that preceded the wider collection of stony corals as the new disease spread along Florida's reef.

WLRN's Nancy Klingener spoke to Karen Neely — the lead author of the paper and a coral ecologist with Nova Southeastern University.

WLRN: What was it like when stony coral tissue loss disease came along a couple years ago and basically wiped out these corals that were already struggling? I imagine you and other divers kind of felt like you kind of got to know some of those coral colonies.

NEELY: We did get to know some of these colonies. We've worked a lot with them for many years. We've done coral spawning with some of them. We named some of the ones that were a little bit more charismatic. There was a big beautiful pillar coral with an arch in it. We named him Archie. There was a pillar coral that had two little pillars sticking out of a nub. We named him Bunny. So we had Lonesome Larry off of Long Key. Pillar Coral forest was off Key Largo. You develop a personal connection with your backyard and with places that you visit a lot and that you love. And to watch them fall apart in such a short period of time is really devastating.

Toward the end of the study you write that they are "functionally extinct on the Florida reef tract with no ability for natural recovery." That's grim. Was it hard to bring yourself to acknowledge that?

It is grim. It was not hard to acknowledge because the data is very clear. But it was very hard to watch. I don't think anybody would relish watching a species diminish into extinction and we had the unfortunate opportunity to do so. And I think as a result we have the responsibility to tell that story.

Before the stony coral tissue loss disease really took hold, you were already working on trying to help pillar corals during the annual coral spawn right?

Yeah, that's right. So we worked with pillar coral spawning for seven years. Because these individuals are so spread out on the reef, it is essentially impossible for them to have successful fertilization in the wild. The odds of the eggs from one individual, and the sperm from another individual, successfully meeting up out there in the middle of the ocean are infinitesimally small with the distance between them. And so we were assisting with that.

We would put divers on each individual colony and collect the eggs or sperm as they were released, race them back to the boats, race the boats across the ocean to meet up with each other and then mix those eggs and sperm in buckets onboard the boat in order to achieve successful fertilization.

But there, unfortunately, are not enough pillar coral in the wild in Florida to continue that work on the reef anymore. But fortunately, our partners at the Florida Aquarium really took this research and ran with it. And as part of the response to the losses to pillar coral, we initiated a pillar coral rescue program where fragments of individuals were brought on shore and Florida Aquarium used those individuals to figure out how to induce spawning of pillar coral in the lab. And so the last year that we were able to do pillar coral spawning in the wild was the first year that they were able to do it in the lab and really had great success and are continuing that work and I really do think that that's the future for this species.

So you can see a future where they can be transplanted back out onto the reef?

I don't know if I will see that in my lifetime. But certainly we've provided the door for that to happen. There are, I think, 400 or 500 fragments of pillar coral that are being held in our various facilities. The spawning of them improves every single year and there are hundreds of babies that have been born as a result of this. And all of this population continues to grow on land. And the goal for that is to have the material to put back out on the reef when the conditions are right to be able to do that.

Copyright 2021 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM. 9(MDAyMTYyMTU5MDEyOTc4NzE4ODNmYWEwYQ004))