In Texas, a proposal to cut the amount of crude that oil companies are allowed to pump from the ground appears dead. The regulator who proposed it — Texas Railroad Commissioner Ryan Sitton — says commissioners "still are not ready to act" on the plan, which would have cut production 20% to try and stabilize prices amid a historic oil glut. Regulators had been expected to vote on the plan Tuesday.

Oklahoma and North Dakota have also been debating production limits. In Alaska, the private company that runs the Trans-Alaska pipeline has already imposed a ten percent cut in oil production from the state's North Slope.

In Texas, the idea of a state intervention would have been unimaginable to most people just a few months ago, even though it's not without precedent. Somewhat confusingly, the Texas Railroad Commission oversees fossil fuel extraction, and has the power to limit crude production under a law dating back to the 1930's. It hasn't done so since 1972.

But even if such a vote does not happen, the fact that the three member commission considered the proposal reveals just how serious the challenges facing the U.S. oil and gas industry are.

An industry divided

At a hearing last month, Scott Scheffield, head of Pioneer Natural Resources, said it was time for the commission to mandate cuts again. He argued that his industry — which has enjoyed unprecedented expansion in recent years — couldn't be trusted to cut enough on its own.

"Our industry has created so much economic waste that nobody will buy our stocks or own ours stocks," Scheffield said in a live-streamed meeting. "If the Texas Railroad Commission doesn't regulate long-term, we will disappear like the coal industry."

But companies and regulators are divided over imposing production limits. Opponents say companies are making needed cuts on their own. They don't want to open the door for government control of industry.

If the Texas Railroad Commission doesn't regulate long-term, we will disappear like the coal industry.

"It is government intervention itself that would cause haphazard curtailment of production and cause waste," argued Todd Staples, head of the Texas Oil and Gas Association. "Texans fundamentally believe that the government should not be in the business of picking winners and losers."

So, who stands to win and who stands to lose?

Owen Anderson is an oil and gas law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He says large oil companies, so-called supermajors, that not only produce oil but also transport it and refine it, are better positioned to weather this historic bust. They tend to oppose the intervention.

"They're probably looking at this downturn as a buying opportunity," says Anderson, "because they have some capital assets that they could devote to buying up companies and properties, probably for bargain basement prices."

Smaller, so-called independent oil producers, were struggling with debt even before prices crashed. They don't have the same access to pipelines and refineries and believe that if everyone is forced to cut a little, it may allow them to keep producing some oil. If the state doesn't act, they say, this is an oil bust they might not survive.

"And they've got good reason to be concerned," says Anderson, "probably more reason now than they have in the past."

As it turns out, this division between big oil companies and small "independents" is exactly what drove Texas to first regulate oil production during the Great Depression.

Shutting down oil wells at gunpoint

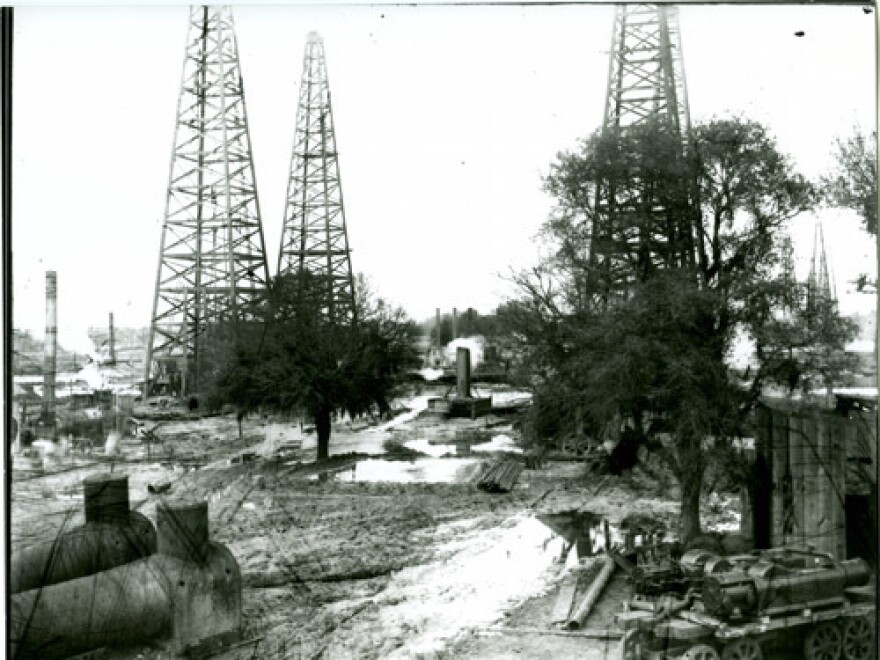

In East Texas in 1930, the discovery of the biggest U.S. oil field at the time set off a rush. Hundreds of wildcatters leased tiny plots of land from local farmers. "A lot of them were just gamblers," says Don Carleton, director of the Briscoe Center for American History.

But they kept striking oil. There was too much of it to store and no easy way to get it to market. And there was another problem that resonates today: This was all happening during the Great Depression, so demand for oil had cratered. Prices plummeted to as low as five cents a barrel.

By 1931 the big oil companies were demanding action. The Texas Railroad Commission ordered the wildcatters to stop pumping, but it didn't go over well.

"All of the small independents rebelled, and just simply thumbed their noses," says Carleton. They said, "'Oh yeah, you and whose army is going to stop us?'"

That's when Texas Governor Ross Sterling sent 800 National Guardsmen and a company of Texas Rangers to the East Texas Oilfield.

The guardsmen "would literally have to pull out their rifles with bayonets to go and make sure that their wells were shut down," says Carleton.

From the 1930s until 1972, essentially, the [Texas] Railroad Commission was the most important institution in the world of oil.

After several months, the troops were replaced by Railroad Commission staff. But the conflict wasn't over. This was happening during prohibition and a lot of people had become very good at transporting illegal liquids.

"These little refineries... they'd pay cash for the oil when it came in, and they sold the gasoline for cash so there's no record of anything," recalled Joe Kinsey decades later for an oral history project at Stephen F. Austin State University.

Kinsey remembered how producers also created fake oil wells to launder illegal crude, and drilled holes in pipelines to sneak it away.

The Texas origins of OPEC

Eventually the Texas Railroad Commission managed to gain control. As its power grew it started working with other states to set production levels and prices.

"From the 1930s until 1972, essentially, the Railroad Commission was the most important institution in the world of oil," says David Prindle, a professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin who wrote a book on the commission.

Prindle says in 1951 the head of Venezuela's energy sector looked to Texas for inspiration.

"He hired the chief engineer of the Railroad Commission... to come to Venezuela, to come show him, and then show the oil minister of Saudi Arabia, how it was done," says Prindle. "OPEC was explicitly modeled on the Texas Railroad Commission."

As more oil was discovered around the world OPEC gained power and the Railroad Commission lost it. The commission stopped capping Texas production in the early 70s.

"A lot has changed"

Now, an economic crisis and a huge glut of oil are forcing the issue again. It's a situation a lot like the one that existed in 1931, except large and small oil companies find themselves on opposite sides.

"That's, from an historical perspective, rather interesting," says UT-Austin's Anderson. "In the 1930s, it was mostly the larger companies that were clamoring for a lowering of production in the United States, and the small independents were mostly resisting it."

While last century's wildcatters may have preferred pumping cheap oil to pumping none at all, these days independent producers say they don't have that choice. With storage space filling up fast and pipeline access limited, some say they will not be able to bring their oil to market unless cuts happen across the board.

"The bigger guys have plenty of market, plenty of pipeline access and plenty of ways to store their oil, independents do not," Kirk Edwards, head of Latigo Petroleum told the Railroad Commission last month. "If there's not some way to allow fairness then you will personally be responsible for the demise of the Texas independent producer this year."

Texas Railroad Commissioner Sitton, who proposed cutting production to address today's crisis, suggested it could save jobs. But commission chair Wayne Christian says "a lot has changed" since the state last capped oil production.

"In 1950, Texas controlled over 20 percent of the world's oil supply, today we control roughly 5 percent," he wrote in the Houston Chronicle. "A government mandate cutting oil production twenty percent across the board would not have a significant impact on worldwide oil supply."

The commissioners had all agreed that they'd want other states to make similar commitments, and would need Russia and OPEC countries to promise even deeper cuts than the record ones they already have.

Meantime, the current bust in the always turbulent U.S. oil industry may deepen. Dozens of Saudi tankers full of oil are offshore or headed this way. Companies say there could soon be so much excess oil that they will run out of places to store it.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAyMTYyMTU5MDEyOTc4NzE4ODNmYWEwYQ004))